Chapter 2 Adagio

George Worgan, his musical family, and connections to the Longman & Broderip Company

George Worgan (1757-1838) was the son of John and Sarah Worgan. George Worgan had two brothers – Richard (1759-1840) and James (1762-abt. 1802) who were musicians. His half-brother Thomas Danvers Worgan (1774-1832) was a composer-musician1.

Dr John Worgan (1724-1790), a Doctor of Music, was in his heyday a composer, as well as a highly accomplished organist, who played at the Vauxhall Gardens in London. John Worgan lived his life within 20 to 30 minutes walking distance from 13 Haymarket, and the premises of the Longman & Broderip Company during the 1780s. John & Sarah Worgan’s marriage bond (1753) states that John Worgan was living at Clement’s Inn. In 1757 and 1759 respectively, George Boucher Worgan and his brother Richard were baptised at the church of St Andrew, Holborn, London, as were all John Worgan’s children up to 1764. This address – I presume the family lived near the church – is about a 20 minute walk from 13 Haymarket, but a bit further to Cheapside, the other premises of Mr Longman’s company which had a number of different titles, depending on the business partner/s of the time. In 1768 another son of John Worgan was born at Bedford Row, Middlesex – that’s about half way between Cheapside and Haymarket. From 1773 to 1784, John Worgan was living at Marylebone, according to tax records and the birth record of his son Thomas Danvers Worgan (1773). John Worgan died about 1790 at 22 Gower St, London (about a 20 minute walk to Haymarket).

John Worgan had a special relationship with the Longman & Broderip company as they published his musical compositions. The company only later branched in to the business of selling pianos; prior to that they published sheet music. When Longman & Broderip went bankrupt about 1797, Musio Clementi rescued it as Longman, Clementi & Co. Later, the company employed the composer John Field, who is acclaimed as being the inventor of the musical form that Chopin championed – the nocturne. Clementi and John Field travelled as far away as Russia, and they took a piano from the Clementi (aka Longman & Broderip) company with them. Here are two connections – that of Dr Worgan having his music published by Longman & Broderip, and the company’s enthusiasm for sending square pianos to distant parts. The possibility remains that the Longman & Broderip company gave or sold a basic piano to John Worgan’s son specifically for his trip to NSW.

George Boucher Worgan’s life during the time the first fleet piano was bought is described in the Australian Dictionary of Biography:

At 18 he entered the navy, qualified as surgeon’s second mate in February 1778 and was gazetted naval surgeon in March 1780. He served for two years in the Pilote and in November 1786 joined the Sirius, sailing in her next year in the First Fleet to New South Wales and taking with him a piano 2

In putting a piano on board one of the ships of the First Fleet, what were they thinking? Why would a piano be included on the cargo of the first fleet, when space was mostly filled with what were considered to be essential items needed to establish a British colony on the other side of the earth – items such as livestock, provisions, plants and seeds? No one really knows why. The whole enterprise of moving convicts to the antipodes was to colonise the land, thus increasing the power and influence of the British Empire. With that in mind, maybe it was thought the piano would have a civilising effect.

The piano and the elements at Sydney Cove

In the 1780s in England, pianos were a luxury item. Why, if you were off to an uncertain future in the antipodes, would you buy a new piano, especially one (as claimed by Geoffrey Lancaster) with precious Tunbridge-ware marquetry and cabriole legs (that would surely have been damaged on a sea voyage) and then leave it behind? Even after arriving in 1788, conditions were pretty uncomfortable. There are no specific records about how the piano was kept out of the rain. The Dictionary of Sydney tells us that…

When Phillip moved on shore in February 1788, he took up residence in a portable canvas house erected on the eastern side of what was to become known as the Tank Stream. A prefabricated dwelling of timber-framed panels covered with oilcloth, it cost £130 – a third of the amount paid for all the marquees and camp equipment for the marine officers. Forty-five feet long, 17 feet 6 inches wide and 8 feet high (13.7 metres long x 5.3 metres wide x 2.4 metres high) it had a wooden floor, five windows each side, 3 foot 9 [inches] by 3 foot [1.1 x 0.9 m] and was divided internally. Often referred to as a tent, although it proved ‘neither wind nor water proof’, it was actually rather impressive.3

Was the piano stored at “Government House”? Or was there other storage in another tent? Eventually, the piano must have been moved to shore as we know the movements of the Sirius, Worgan’s ship. Wikipedia tells us that the

Sirius left the colony at Port Jackson on 2 October 1788 when she was sent back to the Cape of Good Hope to get flour and other supplies. The voyage, which took more than seven months to complete, returned just in time to save the near-starving colony.4

The piano was almost certainly off-loaded before 2 October, to maximise space for the supplies needed. If it was October 1788 that the piano was off-loaded, it would have been just in time for the spring rain. The piano had to compete with other items, such as clothing, flour, sugar and seed corn, for the scarce resource of good shelter. A valuable instrument with delicate Tunbridge-ware marquetry, especially made for Mr Worgan with unusual folding cabriole legs (if this is true) was at risk of being seriously damaged if the piano got wet. There was a good chance of the animal glue holding it all together dissolving, and the delicate finish being ruined, not to mention the piano going out of tune. In the best of conditions, square pianos need tuning every six months, and these were by far not the best of conditions! For extra information about tuning a square piano, I commend Tuning Ancient Keyboard Instruments: A rough guide for amateur owners by David Hackett5 To get the pitch, the piano tuner would need to use a tuning fork or a wind instrument. We do not know who tuned the first fleet piano, but without doubt George Worgan would have been the piano tuner while it was in his ownership. After Worgan’s departure, the band-master repaired and tuned it.6 An alternative possibility for the piano-tuner is that the anonymous individual placed on government rations in 1800 to maintain musical instruments … in his spare time could have worked for the general public.7

The colony was struggling to accommodate the 1,000 people who had arrived. Just to provide food and shelter was a struggle. The weather in Sydney was (and still is) hot and humid in summer and cold and damp in winter. It can also be very dry at times. Then of course there were the convicts, not all of whom were particularly cooperative. In June 1788 four cows and two bulls got loose and could not be found, meaning less food was available. It seems to me that by October 1788, that piano was just about more trouble than it was worth! No wonder George Worgan gave it to Mrs Macarthur not long after she, her husband and their infant son arrived on the second fleet in June 1790. The piano would have a reasonably dry and safe home.

Elizabeth Macarthur’s correspondence is the source used for the numerous accounts of her life in the colony8. Not long after they arrived, John Macarthur fell ill from a fever, and Mrs Macarthur sought support from friends, two of whom were surgeons John Harris and George Worgan. The next mention of the piano is in Elizabeth Macarthur’s letter – George Worgan started giving her lessons on it and he taught her to read music, as a distraction from her worries.

On 7 March 1791, Mrs Macarthur wrote to her friend Miss Kingdon:

I shall now tell you of another resource I had to fill up some of my vacant hours. Our new house is ornamented with a pianoforte of Mr. Worgan’s; he kindly means to leave it with me, and now, under his direction, I have begun a new study, but I fear without my master I shall not make any great proficiency. I am told, however, that I have done wonders in being able to play off God Save the King and Foot’s Minuet, besides that of reading the notes with great facility. In spite of musick I have not altogether lost sight of my botanical studies . . .9.

In the autumn of 1791, George Worgan left the colony never to return. Around that time, he gave the piano to Elizabeth Macarthur.

The Macarthur piano after 1793

The Macarthur family moved to Elizabeth Farm in November 1793. We know the piano went with the Macarthur family to Parramatta. No record of any communication between George Worgan and Elizabeth Macarthur has been found. Once George Worgan was on his way back to England, he probably considered that the piano was for Mrs Macarthur to look after!

We do not know what condition the Worgan piano was in by 1810, but it is quite likely that it would have warped by then, especially in the prevailing climate. Many square pianos of that era warp. They have brass and mild steel strings tightly stretched diagonally across the wooden frame. The hotter and more humid the climate, the more the piano will warp. That would not necessarily make the piano unplayable, but it may no longer sit evenly on its legs or stand, and it would not be up to scratch in a respectable household. If the piano continued to be tuned and generally cared for, it may have survived, even if warped. A more likely scenario is that one or more of the piano strings broke and could not be replaced.

We hear nothing about that piano or any other piano until 1810, when Mrs Macarthur is said to have purchased a second-hand piano for £85, which was a lot of money at the time. According to one calculator10 it is worth about $25,000 today. Mind you, a new Steinway grand piano today costs about $80,000, or you can pay up to $17,000 for a new upright piano. So £85 would buy a top-end make and model. This was certainly not a top-end model. As distinct from George Worgan’s piano that became Mrs Macarthur’s first piano, we know a bit more about Mrs Macarthur’s second piano. It was no doubt better than the first, but not anything special. I am grateful for the research presented on the AustralHarmony website11.

Thomas Laycock’s piano (1799-1809) Quartermaster, New South Wales Corps, 1791-1808, Deputy Commissary, NSW, 1794-1800 … Broadwood archive, porters book, 10 April 1799 ((ref. 2185/JB/42/1) A SPF add ff 4362 and cover, addressed Mr. Thomas Laycock, Deputy Commissary, NS Wales, delivered to Farlow to be shipped on board the Ann, Captain Dennet. [Note in margin of entry shows the piano was £27.6, cover £1.2, strings £1.3 [presumably spare set – this is not uncommon for pianos going overseas], tin case £1.11.6, deal case 13s, shipping and wharfage, 8s 6d, total £32.4].

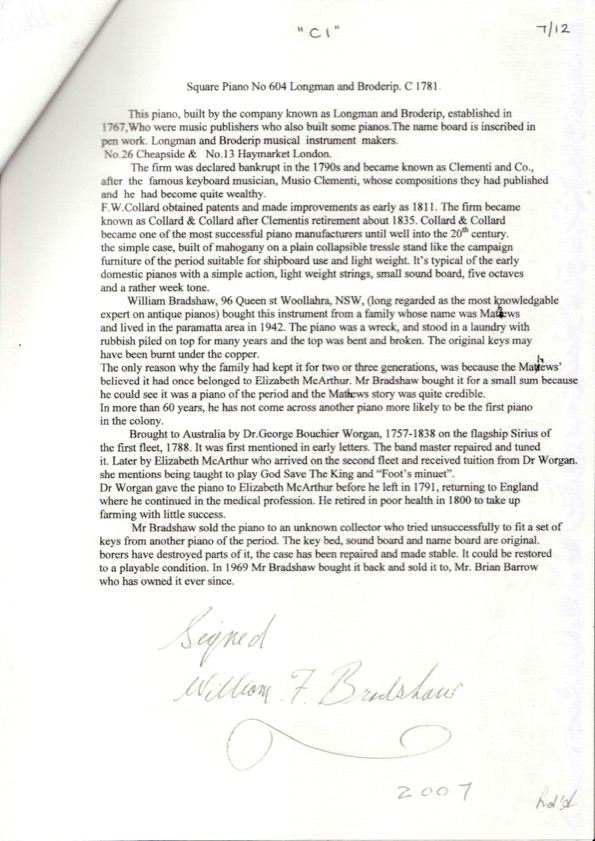

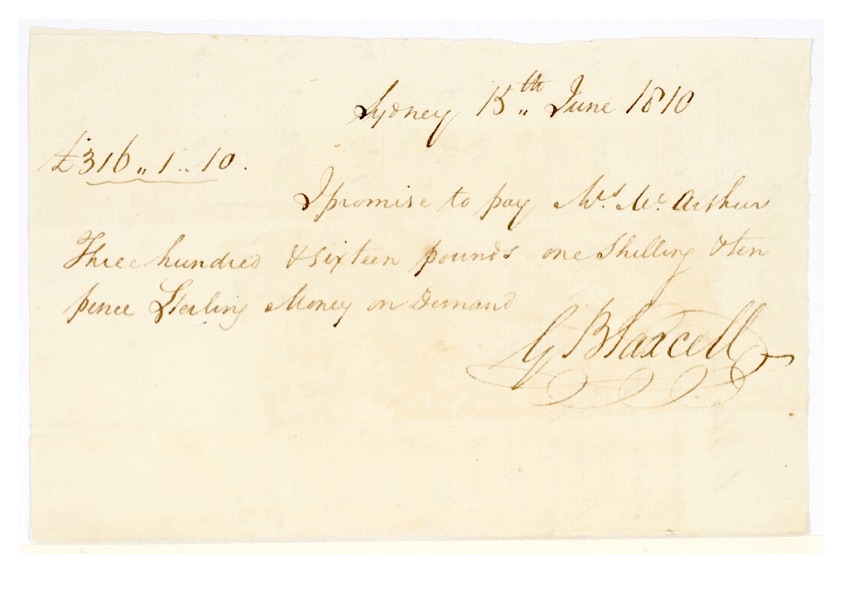

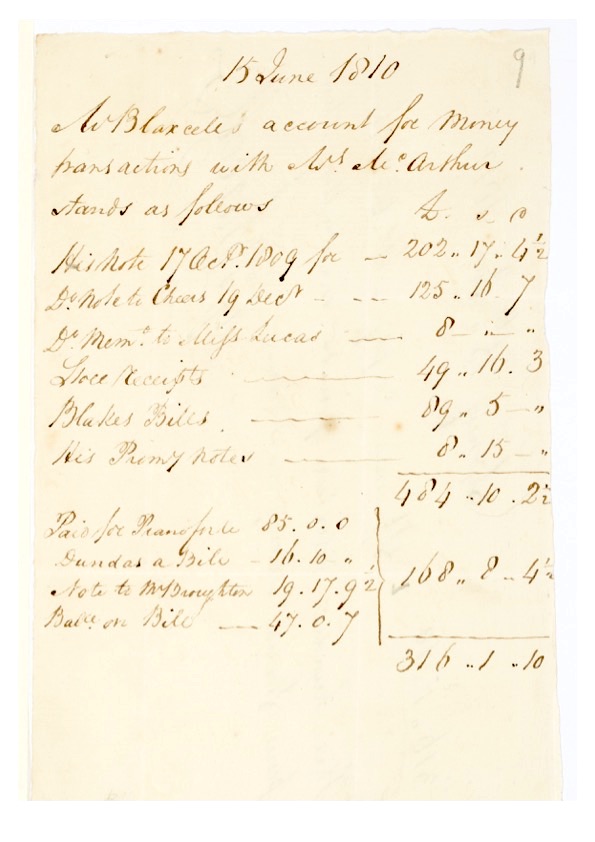

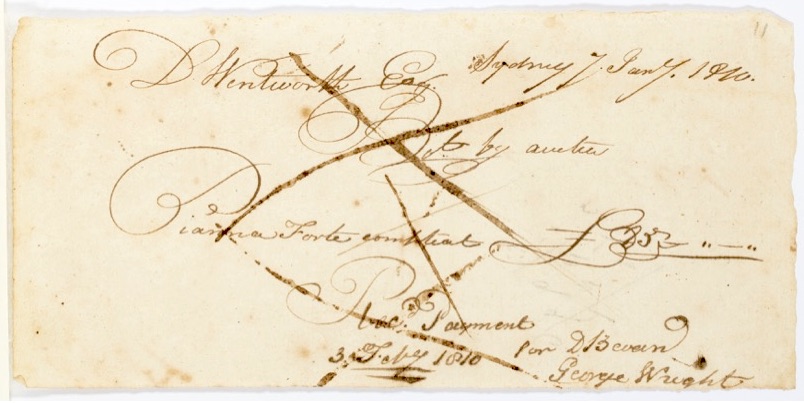

Thomas Laycock paid a total of £32/4/- for his piano. “SPF” means square piano forte, “add ff” refers to the extra half-octave, introduced in 1793/4, that was becoming common by 1799. When there are five octaves, the top note is an F. The extra notes took it to C.12 The pianoforte was shipped to him in 1799. To have that piano inflated to £85 eleven years later, is really to be questioned. Laycock died on 27 December 1809.13. On 31 December 1809, his household effects were advertised for sale by auction set for 4 January 1810. The Macarthur family papers contain a document that suggests that the price of the piano that Mrs Macarthur bought in 1810 was, in fact, £25 not £85.14 The bill of sale from the Macarthur Papers is shown below. The people involved were D’Arcy Wentworth, the Trustee of Thomas Laycock’s estate, Mr Bevan, who seems to have organised the sale. Also involved was Garnham Blaxcell, the sole auctioneer of the colony.

The bill of sale above shows that the sum paid at the auction was £85, but on close inspection it appears that it was actually £25. The bill of sale appears to have been altered by a squiggle over the 2 of the 25, which makes the figure look like an 8. Note the way the date “1810” is written. The “8” in that looks nothing like what is purported to be an “8” in the sale price. To explain, Blaxcell15 had been keeping some accounts for Mrs Macarthur. He handed her a statement which included the cost of the piano, no longer £25 but £85. It is shown below with another document from Blaxcell that states that he owes Mrs Macarthur £316/1/10; note a higher sum had been defrayed in part by the false £85 price tag on the piano. For an ordinary worker, this must have been huge sums of money. Either Garnham Blaxcell defrauded Mrs Macarthur, or it was just a mistake, but it at least explains the huge cost of a fairly ordinary piano. Did Mrs Macarthur notice she had paid way too much for her second piano? I would hazard a guess that if she wrote to Blaxcell, that letter would not have survived. Blaxcell was later sacked as Mrs Macarthur’s accountant. The Australian Dictionary of Biography says,

As early as 1809 unsuccessful speculation in trading had obliged [Blaxcell] to assign his Drainwell estate to Surgeon Thomas Jamison. In 1810 he became further involved in debts to John Macarthur and other leading colonists, and by 1812 he was unable to meet liabilities for import duties. His finances steadily worsened …16

In 1811, Elizabeth Macarthur replaced Garnham Blaxcell with another accountant. It is quite possible that Elizabeth Macarthur was aware of the fraud (or mistake). There is no indication it was corrected, but it seems unlikely as Blaxcell’s debts to John Macarthur had increased somewhat. By 1817, Blaxcell’s finances had considerably worsened and he was required to appear at the Supreme Court regarding his debts to the Government. He skipped out of town on the Kangaroo, but died at Batavia on 3 October 1817, his death being partly due to overconsumption of alcohol.

In NSW history, this was a turbulent time. The 1808 rum rebellion resulted in Governor Bligh being deposed. In 1810, John Macarthur had been authorised to travel to England along with other rebels who intended to support Major George Johnston in presenting his defence for deposing Governor Bligh. There is no room to go into the details of the rum rebellion here! Wikipedia has a good summary. But Mrs Macarthur did not have her husband’s company, and she managed his estates extremely well, under the circumstances. She hardly had time to worry about selling an old piano of very little value. Geoffrey Lancaster, in chapter 14 of his book asserts that Mrs Macarthur sold her piano.17 This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 of this article.

See chapters 3 and 4 for more!

This article will be updated when new material comes available.

Attachments as discussed:

- Graeme Skinner, http://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/worgan-family.php, accessed 9 October 2018

- John Cobley, Australian Dictionary of Biography http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/worgan-george-bouchier-2816

- Jane Kelso, The First Government House: building on Phillip’s “good foundation” (2018) https://dictionaryofsydney.org, accessed 20 September 2018. I have amended the dimensions of the windows as in the source they are converted to metric measurements incorrectly.

- Wikipedia, HMS Sirius (1786)(2018) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Sirius_(1786)accessed 20 September 2018

- David Hackett, http://www.friendsofsquarepianos.co.uk/care-and-restoration/ accessed 29 September 2018.

- Statement by Bill Bradshaw not dated, but most likely date is August 2007. See statement at foot of this page.

- Robert Jordan, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 98, part 2, page 198.

- Lennard Bickel, Australia’s First Lady, (1991,) Allen & Unwin Australia Pty Ltd., Hazel King, Elizabeth Macarthur and Her World, (1980) Sydney University Press, Sibella Macarthur Onslow (ed), (1914) Some Early Records of the Macarthurs of Camden,Angus & Robertson Ltd., Michelle Scott-Tucker, Elizabeth Macarthur. Life at the Edge of the World(2018) Text Publishing, Melbourne, Vic., James Broadbent & Joy N Hughes, Elizabeth Farm, Parramatta: A History and Guide(1984) Historic Houses Trust

- Graeme Skinner, op. cit., accessed 10 October 2018

- https://www.measuringworth.com(2018) accessed 20 September 2018.

- Graeme Skinner, http://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/broadwood-pianos-in-australia.php, accessed 8 October 2018

- David Hackett, Personal communication 19 October 2018

- Laycock, Thomas (1756–1809)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/laycock-thomas-2339/text3049, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 20 September 2018.

- Macarthur Family Papers 1789-1936, 1stcollection State Library of NSW, call #A2909/vol13, pp 9-11 7 Jan 1810

- Macarthur Family Papers 1789-1936, op. cit., pp 9-11

- E. W. Dunlop, ‘Blaxcell, Garnham (1778–1817)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/blaxcell-garnham-1794/text2029, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 30 November 2018.

- Lancaster, The First Fleet Piano: A Musician’s View ANU Press 2015, Vol 1, chapter 14, page 671.