The first Commonwealth Games to be held in Australia opened just over 80 years ago, at the Sydney Cricket Ground on Saturday 5 February 1938

Known then as the British Empire Games, (and dubbed the “Empiad” by the Press) this was the third of the Games to be held, the inaugural one having been in 1930 at Hamilton, Ontario, in Canada, followed in 1934 at London. The choice of Sydney for the 1938 Games had been agreed as part of Australia’s celebrations for its 150th anniversary since the arrival of the First Fleet at Port Jackson in 1788.

While the current Games at the Gold Coast is hosting over 70 nations competing in 18 sports, the 1938 event had a more modest gathering of 15 nations, who took part in just seven sports over the twelve days from the 5th to the 12th of February. These were athletics, boxing, cycling, diving, lawn bowls, rowing, swimming, and wrestling. The team sizes ranged from Australia’s 178, to the specialist contributions of those such as British Guiana (Guyana) in the cycling, Fiji in lawn bowls, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), whose Barney Henricus won a gold medal in the featherweight boxing. Women participated in the aquatic and some athletic events; the remainder, including lawn bowls, were reserved solely for men.

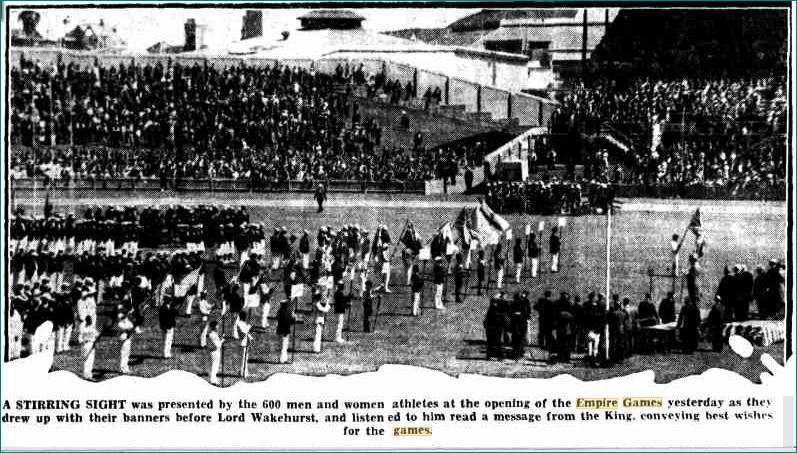

Over 35,000 people watched the opening Ceremony, which began at 2pm on a sunny Saturday afternoon. The Governor, Lord Wakehurst read a message (see footnote below) from King George VI, [Fig.1, above] and 2000 pigeons (representing doves of peace) were released to mingle with the displays of colourful balloons. The competitors had marched, all dressed in white, apart from their colourful national blazers, around the arena [Fig.2] before listening to the message, and then the Australian team leader, cyclist Edgar (Dunc) Gray read out their “Oath of Amateurism”. The choir sang “Rule Britannia”, the Officials departed, and at 3pm, without more ado the Games began, with the men’s and then the women’s 100 yards running heats. In the evening, a swimming carnival was held at the recently opened North Sydney Olympic pool.

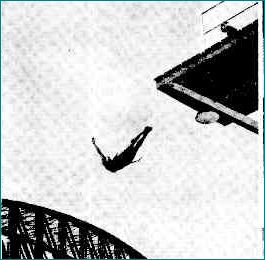

This dignified, if rather low key, ceremony was quite a contrast to those in later decades, when the advent of television and colour cinema demanded more spectacular entertainment. [Fig.4] However, the 1938 games did get prolific media coverage from the many radio stations and local newspapers that were then available.

While the majority of the games were based at the Sydney cricket ground, [Fig 5] other venues were also used, that were not only appropriate to the needs of the sport, but had been recently opened or built. This was a good opportunity to show the visitors Sydney’s sports facilities that had been achieved despite the recession, as well as providing more spectator opportunities for the residents of the local suburbs involved.

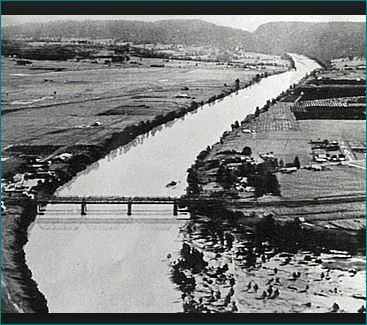

The rowing events were held 50 km to the west of Sydney, on the Nepean River at the foot of the Blue Mountains [Fig 6], rather than on the tidally unpredictable (and occasionally shark infested) Parramatta River. The rowing competitors all stayed at the Lapstone Hill Hotel, a former mansion called “Logie’, which had opened as an Art Deco style hotel in 1930. [Fig 7]

Henson Park (formerly Thomas Daly’s brickpits) at Marrickville in Sydney’s southern suburbs was the venue for the cycling. [Fig 8] Named for a locally prominent family, it had opened in September 1933 with a cricket match, one of the players being Don Bradman. The finals of the longer race (100km) were held at Centennial Park, (but only after the hazards of the jutting trees on the course had been sandbagged to the satisfaction of the cyclists’ team manager) [Fig 9] It was also the venue for the closing ceremony of the games.

On Sydney’s North shore, just to the west of the northern approaches of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (opened in March 1932) the recently opened Olympic Pool (April 1936) was used for the swimming and diving events, [Fig 10] while the boxing & wrestling matches, due to unexpectedly large entries, evoked last minute pleas from officials to Leichhardt Stadium managers, before the Rushcutters Bay Stadium was settled on.

The victory ceremonies provided an opportunity for spectator participation, as they sang along with the choir the various national anthems of the winning country – when they knew it! Australian victors were greeted with “Advance, Australia Fair”, while the English winners were given a hearty rendering of “There’ll always be an England”.

Apart from the gold, silver and bronze medal, there were numbers of souvenir and participants’ medallions. A particularly well-thought-out and interesting one mostly diverged from the usual themes of classical figures and laurel wreathes, and instead on the front (obverse) depicted Sydney Harbour bridge as a symbol of the game’s main purpose; that of ‘bridging the gap’ and reinforcing friendship among the nations of the Empire. [Fig 11] It also showed the seven sports in a slightly stylised form, which may have been one of the earliest forerunners of the pictograms now used. There were also badges worn by each national team member, with an appropriate symbol, such as Canada’s badge in the shape of a maple leaf [Fig 12]

Many of the foreign and interstate competitors were accommodated in a temporary ‘village’, which was erected in the Sydney show ground [Fig 13] – although this courtesy did not apparently extend to the NSW country members of the team, which gave rise to a few grumbles, much to the delight of some of the more sensational newspapers, who enjoyed high-lighting any perceived defects in the arrangements made by the officials and organisers.

The closing ceremony took place on Monday 12 February 1938, at Henson Park, by which time Australia’s tally of medals had reached 66, of which 25 were gold; the runner up was England, with 40 medals, including 15 gold.

Footnote:

The Governor of NSW His Excellency Lord Wakehurst read a message from King George VI and also welcomed the teams. The message read:

“I shall be grateful if you will express to all participating in the British Empire Games my hearty thanks for their loyal assurances. I send my best wishes for the success of the Games, the results of which I shall follow with interest and I am particularly glad to know that they have attracted to Sydney the representatives of so many parts of the Empire – George, R.I.”

This tradition of a message from the monarch continues today and in 1958 the Queen’s Baton Relay was introduced for the Cardiff Games.

Other websites: